Almost four years have passed since the public lynching of George Floyd at the hands of police in Minneapolis. Today, after myriad calls for architecture as a discipline to reckon with white supremacy and colonialism since 2020, we, the current ACSA Fellows to Advance Equity in Architecture, contend that we’re unfortunately in a worse place.

Why? If 2020 was marked by numerous calls for decentering the whiteness of Eurocentric and U.S.-centric bodies of knowledge and approaches to the built environment, the events of late 2023 and early 2024 have forcibly recentered European and U.S. prominence in the worst of ways.

Institutions on both sides of the Atlantic have censored speech as we helplessly witness, and involuntarily participate, in the broadcast and relentless destruction of human life in Palestine, in addition to the region’s architectures and infrastructures. Certainly, when Angela Davis—the prison abolitionist, antiracist scholar, activist, and recipient of The Architectural Review’s 2024 Ada Louise Huxtable Prize—recently affirmed “how central the Palestinian quest for justice is to liberation struggles here in the U.S. and in other parts of the world,” she outlined how the searches for liberation around the world are all interconnected.

On polarizing times

Since being awarded the ACSA Fellowship to Advance Equity in Architecture in 2023, we have witnessed numerous occasions of dangerous smearing and doxing. Scholars and students have been targeted in predominantly white institutions, both public and private. People with no previous scholarship on settler-colonialism, and related fields and legacies, target scholars and activists who have invested most of their lives trying to upend, reveal, and subvert these damaging colonial, imperial legacies and ongoing practices.

For instance, a recent piece published on the right-wing outlet NZZ takes aim at Samia Henni, Anne Holtrop, Ariella Azoulay, the feminist collective Parity Group, and other scholars teaching at ETH Zurich who have spoken out against the violence taking place in Gaza. The article, written by a German architectural theorist who teaches in Stuttgart, attempts to trivialize or erase the historical traces and manifestations of colonial violence, oversimplify and discredit the work of anti-colonial scholars, and conflate criticism of state-sponsored military violence with a decontextualized and self-serving definition of a particular form of racism.

The American Association of University Professors (AAUP) already warned us about this type of critique in its 2022 report, “Legislative Threats to Academic Freedom: Redefinitions of Antisemitism and Racism.” The text published by NZZ is an example of gaslighting, embodying a propaganda tactic used by politicians and scholars, without expertise in studies of coloniality and empire, as they try to lecture experts about how they should think about and address the violence of colonialism. We fear that these types of attacks are also part of a dangerous trend that include the recent burglary and vandalization of Samia Henni’s office at Cornell University, which reminds us of when Palestinian professor Edward Said’s office at Columbia University was set on fire in 1985.

Hundreds of years of colonialism have repeatedly shown that antiracist advances are usually followed by white supremacist backlash in the forms of political improvisation, targeted policies, suppression, and persecution. Today, we see more of the same, as calls for justice for the Palestinian people have exacerbated aggressive forms of reactionary opposition to anti-colonial and antiracist scholarship. It comes as no surprise that the more than 30 bills across the U.S. targeting diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives (DEI) at public colleges match the annual average of the 293 bills introduced since 2014 that have targeted advocacy for Palestinian rights.

As the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) affirms in its statement, polarizing times demand robust academic freedom. AAUP states that “many colleges and universities are not only failing to protect academic freedom, they are actively undermining its scope and meaning” giving way to “external political pressures and demands for political censorship instead of encouraging the utmost freedom of discussion.” How should architects and academics respond to this current situation?

A platform and call for justice

Amid these challenges to academic freedom, last month, we launched acsajustice.org—a website that centralizes architectural scholarship and initiatives focused on social and ecological justice. Its goal is to outline the germaneness of these topics to architecture as a discipline, practice, and way of interacting and mediating relationships with the world. This digital project is meant to create a living archive that documents efforts to address social inequality in architecture and architecture education while providing a point of reference where educators, students, administrators, and the general public can find scholarship in the form of publications; other tools of direct action such as demand and solidarity letters; and links to architectural and design education platforms and communities centering their work on social and ecological justice.

With the support of the Journal of Architectural Education (JAE) and Taylor & Francis, we were able to identify over 50 articles, essays, and narratives that deal with social and ecological justice issues and make them freely accessible for at least a year. Even without an ACSA subscription, the general public will be able to access these articles for the first time, including the JAE issue Reparations! that we co-edited with V. Mitch McEwen. Also featured, and in collaboration with Emergent Grounds for Design Education, we were able to include many academic statements, letters, and demands for social justice and antiracist approaches from academic design institutions written in 2020. In addition to these letters, we also mapped anti-Apartheid letters that denounce the ongoing violence, death, and destruction in Palestine; offering a broader international scope to the search of social justice in architecture while reinforcing architecture as a material, historical, ecological, and social practice and body of knowledge.

As a public and accessible resource, acsajustice.org features recordings of lectures, links to open access and freely accessible publications like A Manual of Anti-Racist Architecture Education, Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study, Forensis by Forensic Architecture, and Architecture of the Counterrevolution by Samia Henni, and links to platforms of communities including Dark Matter U, Loudreaders, and Design as Protest, to name a few.

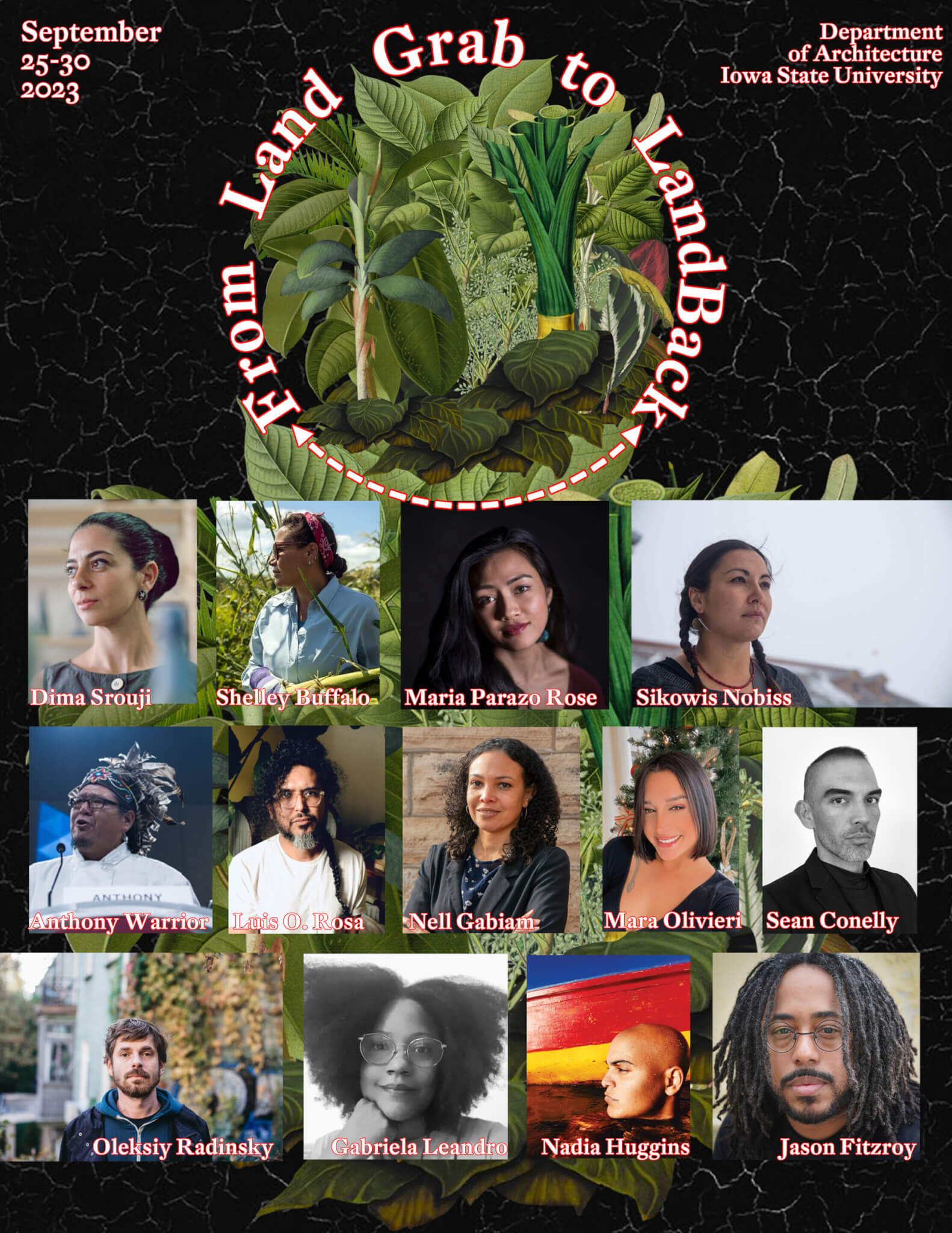

As part of the ACSA Fellowship to Advance Equity in Architecture, we have also developed several strategies that include a traveling series of lectures, symposia, and public events particularly centered on LandBack, abolitionism, and social justice. Co-organized with Women and Gender Studies at the Universidad de Puerto Rico, Iowa State University, Loudreaders, and faculty of the GSA at the University of Johannesburg, From Land Grab to LandBack and From LandBack to Abolition offered a traveling platform for the presentation of urgent positions dealing with occupation, settler-colonialism, and struggles for emancipation and rematriation. Accessible also in acsajustice.org, these series of events included talks, performances, film screenings, and workshops that aimed to set the tone for much-needed conversations.

In a moment when aggressive legislation, political attacks, and doxing campaigns threaten scholarship that seeks justice for all peoples everywhere, including those rendered as less than human by empire, architecture, as the discipline and practice that has historically materialized class, caste, race, and gender inequality, is faced with the imperative to address its own manifestations in legislations of repression, land policies, and zoning laws that reinforce asymmetrical systems and dynamics of power. If Black Lives Matter was, for architectural concerns, centered on the role that prisons, police precincts, and cities play as systematic obstacles to liberation, the international movement of anti-colonial calls from Palestine to Congo, from Vieques to Haiti, further reinforces the urgency of architectural scholarship and practices of design that are free to address the planetary impact of these historically urgent issues.

If 2020 was a year to reckon with the policing and prison system, 2024 has displayed what happens when the logics, infrastructures, and technologies of state, police, and military repression are manifested at both the macro scale of the nation-state, and at the personalized scale of social media. In the architectural dimension, this can help us understand how the prison and policing system—its infrastructures of capture, surveillance, and subjugation—operates not only simultaneously at the scale of the jail cell, prison complex, land subdivision, and the nation-state, but in the architectures of AI (Artificial Intelligence) software for predictive policing and automated bombings. To think of abolition is to think simultaneously about the end of prisons, the end of segregationist policies and practices, and the end of all forms of apartheid, everywhere.

Conclusion

As many short-lived DEI initiatives come to a sudden end in public universities, and as censorship intensifies in private ones, it is time for those engaging with the legacies of the built, destroyed, and imagined environment (to quote professor Samia Henni) to recenter social and ecological justice as a germane and relevant, structural, and unavoidable architectural principle and goal. Rather than letting external and internal pressures render equity as an unattainable or undesirable goal, administrators, educators, and students have a unique opportunity for creatively reinforcing the work of social and ecological justice.

In a time of crushing urgency, as the confluence of ecological and social crises exacerbate via the normalization of the settler-colonial logics of the plantation, military escalation, and extractive cruelty, we must confront the precarity and hostility faced by anti-colonial and antiracist scholars, many of whom work in historically white institutions that would silence or systematically devalue and ignore their very important and necessary work. With interlocking oppressions (to quote the Combahee River Collective) intensifying, the architectures and pedagogies of emancipation demand international and inter-institutional solidarities, platforms, and strategies that reassert academic freedom to research and discuss what makes us unfree. As we test a decentralized lecture series that is open and itinerant as well as a centralized digital archive of justice-related scholarship, we must make these initiatives more a norm than an exception. While we’re all irreversibly transformed by the violence we’re witnessing or living through, we must be able to affirm that there is no future of justice if we’re not all free.

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz Garcia are directors of WAI Architecture Think Tank and associate professors at Iowa State University, where they are Design for Critical Futures in Architecture fellows in Emancipatory Practice and Activism, respectively. They are recipients of the ACSA Fellowship to Advance Equity in Architecture, and teach in the Advanced Architectural Design program at Columbia GSAPP. They also organize LOUDREADERS, a free, alternative educational platform and trade school.