One of the strengths of art historian A.L. McClanan’s newest book is its intention: to provide a historical overview of the many modes in which the legendary creature known as “the griffin” appears in art and literary history. Griffinology: The Griffin’s Place in Myth, History and Art purposefully offers a range of distinct perspectives on various regions and eras to illustrate this mythical creature’s prevalence in the cultural history of ethnoreligious groups around the world.

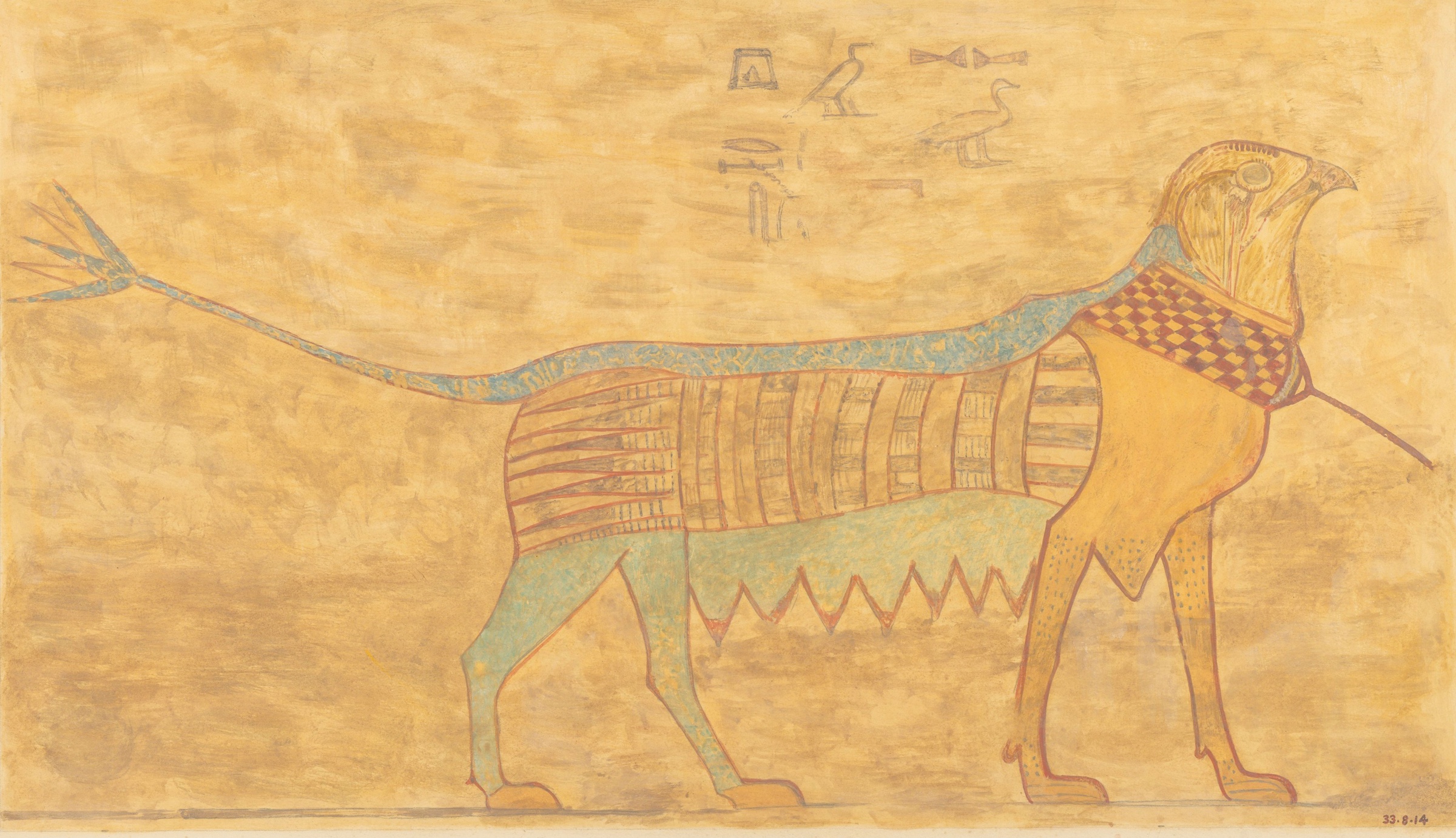

McClanan does not just consider the widely accepted, narrow definition of the “griffin”: namely, a blend of a lion (the ruler of beasts) and an eagle (the ruler of birds). Instead, Griffinology offers a more expansive definition. Spanning some 5,000 years, the text explores various forms and possible combinations of this hybrid motif and how it emerges in the visual language of specific traditions, as well as through their cultural exchange. From South and West Asia to North Africa and Europe, griffins are everywhere: wall reliefs, tombs, tusks, tapestries, drinking vessels, manuscripts, alms purses, and even tattoos. In its assessment of these historical representations, the book draws our attention to the symbolic links between the creature and displays of human power — be it through the built environment of the Byzantine and Sassanian Persian empires, patterns found in Islamic and Byzantine silks, and weapons and armor.

Although Griffinology delivers on its promise to consider both art and literature — including the little-known Gryphon character in Lewis Carroll’s The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland (1865) — the majority of textual examples are limited to the borders of Western Europe. Cited examples of Medieval and modern heraldry and visual branding are also primarily European. Though the creature is acknowledged as an important part of fantasy novels, chivalric tales, and travel writing — including a discussion of its place in popular culture and books such as Harry Potter — these portions of the text could have enriched their argument by incorporating examples from traditions outside of Europe. In the Armenian tradition, a version of the griffin appears in a number of textual and visual examples from the premodern world, and also in coats of arms. The word basguj, most likely from the Middle Persian paškuč, was used to translate the Greek gyrp as “griffin” in the Septuagint. Premodern examples from Arabic and Persian literature also incorporate the creature as a metaphor for power, protection, and the blending of cultures.

Griffins are called by different names and vary in their hybridity across traditions, but they equally carry symbolic and allegorical functions. Though it would be impossible to compile every iteration, Griffinology does provide us with a reasoning: “Many intriguing renderings regretfully had to be omitted, for within this limited space I tried to balance relatively famous works with those less renowned.” The approach to distinguishing between what is relatively renowned and what is less recognized, however, seems to be rooted in a European framework.

Griffinology: The Griffin’s Place in Myth, History and Art (2024) by A. L. McClanan is published by Reaktion Books and is available for purchase online and through independent booksellers.