Strewn along the path to the invention of motion pictures are numerous transitional fossils. Humans experimented with different ways to capture images and manipulate the persistence of vision for millennia before these techniques melded, culminating with the Lumière brothers being falsely accused of terrifying a Lyon crowd with footage of a train. Though the new graphic novel Muybridge is primarily a biography of Gilded Age chronophotographer Eadweard Muybridge (who actually intentionally chose that name), author Guy Delisle makes space for many other shepherds of primordial cinema.

A gallery of figures relevant to the story at the front of the book includes not just Muybridge and his family, but also the Lumières, Edison, Tesla, phenakistiscope inventor Joseph Plateau, kinetoscope developer William Dickson, and more. Some of the most interesting parts of the book follow the threads of the people Muybridge interacted with, sometimes briefly. For instance, after he suffered a serious head injury, he was treated for a time in England by royal physician William Gull, who has over the years been floated as a possible candidate for Jack the Ripper. Muybridge’s longtime patron, the robber baron/ politician/ university founder Leland Stanford, has his own subplot. Not to say that Muybridge’s own story wasn’t colorful — it included murdering his wife’s lover and being acquitted by a jury with the judgment of “justifiable homicide.”

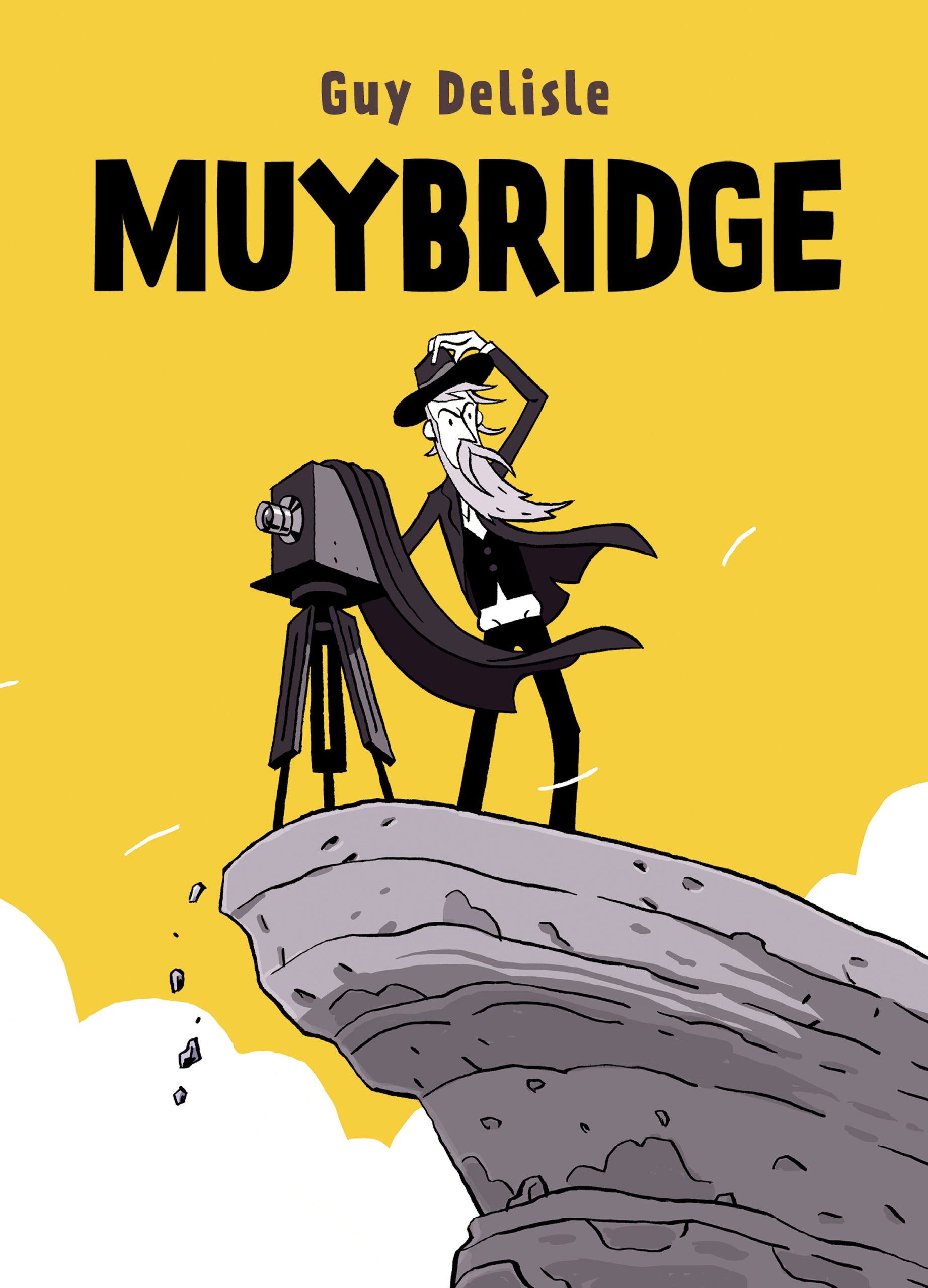

As the above might suggest, Muybridge is as much a social history of photography and its relationship to culture during the 19th century as it is one man’s life story. With cameos from the likes of Charles Baudelaire, Delisle explains how the ability to replicate life in prints affected everything from the art world, as some painters saw their craft threatened, to commercial interests, as the demand for photographs increased. Muybridge entered the business in this context in 1850s California, becoming well-known for documenting “frontier” regions like the West and Alaska, satisfying a market hunger for photography’s perceived capacity to deliver the reality of far-flung places. Delisle’s cartoony style, however, removes any pretension of realism. It is occasionally interrupted by reprints of photos or motion studies, marking a stark divide between “everyday” life as rendered by the pen and life as rendered by the camera.

Indeed, though Muybridge has been the subject of a 1982 Philip Glass opera, a 1975 documentary by film essayist Thom Andersen, and the little-seen 2015 biopic Eadweard, a comic book might be the most suitable medium to explore his work. While we often think of Muybridge’s iconic images of galloping horses or nude subjects in terms of looping movement, they were originally published as sequences of stills. Only later would Muybridge put these series onto zoopraxiscopes to project them for audiences in motion. Before they were early films, they were early comic strips.

At several important moments in this comic book, like the murder or Muybridge’s death, Delisle invokes “slow motion” by imitating the style of the motion studies, breaking down the action into a series of images with minute differences. Arranging the panels alongside each other on the page — their respective images happening both sequentially and simultaneously — encourages the reader to consider each element of a scene, highlighting in particular the different ways that comics and cinema organize time.

This is perfectly in keeping with the spirit of Muybridge’s work. Those motion studies of horses galloping were famously made to settle a bet over whether all four hoofs ever leave the ground at once. He proved that they do, but the full sequence of frames — stitched together first by viewers’ imaginations, and then via zoopraxiscopes, flipbooks, peep shows, and other early motion picture devices — captured the public’s attention even more. In Muybridge, the subject’s work and the biography’s form make a perfect match.

Muybridge (2025), written by Guy Delisle, translated by Rob Aspinall and Helge Dascher, and published by Drawn & Quarterly, is available for purchase online and in bookstores.