On a snowy day in February 1903, a new kind of museum opened in Boston. Despite its plain gray exterior, the institution then known as Fenway Court held a staggering cache of international antiquities and art ranging from Roman times to the present day. Museums were still nascent in the United States, but this one operated differently: Its paintings, prints, sculptures, mosaics, tapestries, furniture, rare books, and other objects were all displayed together in palatial rooms surrounding a lush, Venetian-style garden courtyard that defied Boston’s icy weather. And, until her death in 1924, the museum’s controversial founder lived among her treasures on the top floor.

Renamed the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum after her passing, the institution was the life’s work of an extremely powerful woman who seemed to spark scandal and inspire admiration in equal parts. Her complex and pathbreaking story is expertly explored in Natalie Dykstra’s Chasing Beauty: The Life of Isabella Stewart Gardner, an extensively researched and engaging biography that reveals the many layers of the defiant pleasure seeker, patron, and traveler. The world changed immensely during Gardner’s lifetime, which began before the American Civil War, and she changed with it. But through it all, Dykstra makes clear, Gardner’s mission was to seek, find, and share beauty.

Gardner was born in 1840 to a wealthy family in burgeoning New York City. After studying in Paris, she married one of Boston’s wealthiest and most prominent bachelors, John Lowell “Jack” Gardner. (A 1965 biography, Mrs. Jack by Louise Hall Tharp, takes her husband’s name as inspiration for its title in an antiquated convention that’s happily corrected in Dykstra’s telling.) The transition from cosmopolitan New York and Paris to the more conservative society of her adopted city was difficult for Gardner, but she would later embrace and even court the gossip and attention that her extravagant persona and professional exploits could generate there, from a Boston Globe gossip column on a rumored affair in 1888 to the paper’s front page for her museum’s grand opening over a decade later. After a string of tragic losses including the death of her only son — Dykstra includes some moving excerpts from condolence letters of the time — Gardner dedicated herself to travel as a means to experience and later acquire art.

The couple spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on months-long trips to places like Egypt, Japan, China, and the art centers of Europe. Along the way, Gardner purchased many of the exquisite objects that would eventually populate her museum. Dykstra conveys Gardner’s genuine curiosity about other cultures while pointing to the economic crises, travel trends, and political practices that allowed her and other American elites to essentially plunder global art collections for their own fledgling museums and collections in the US. On these and other occasions, the author thoughtfully critiques Gardner while placing her within a particular context that helps us understand her even more clearly.

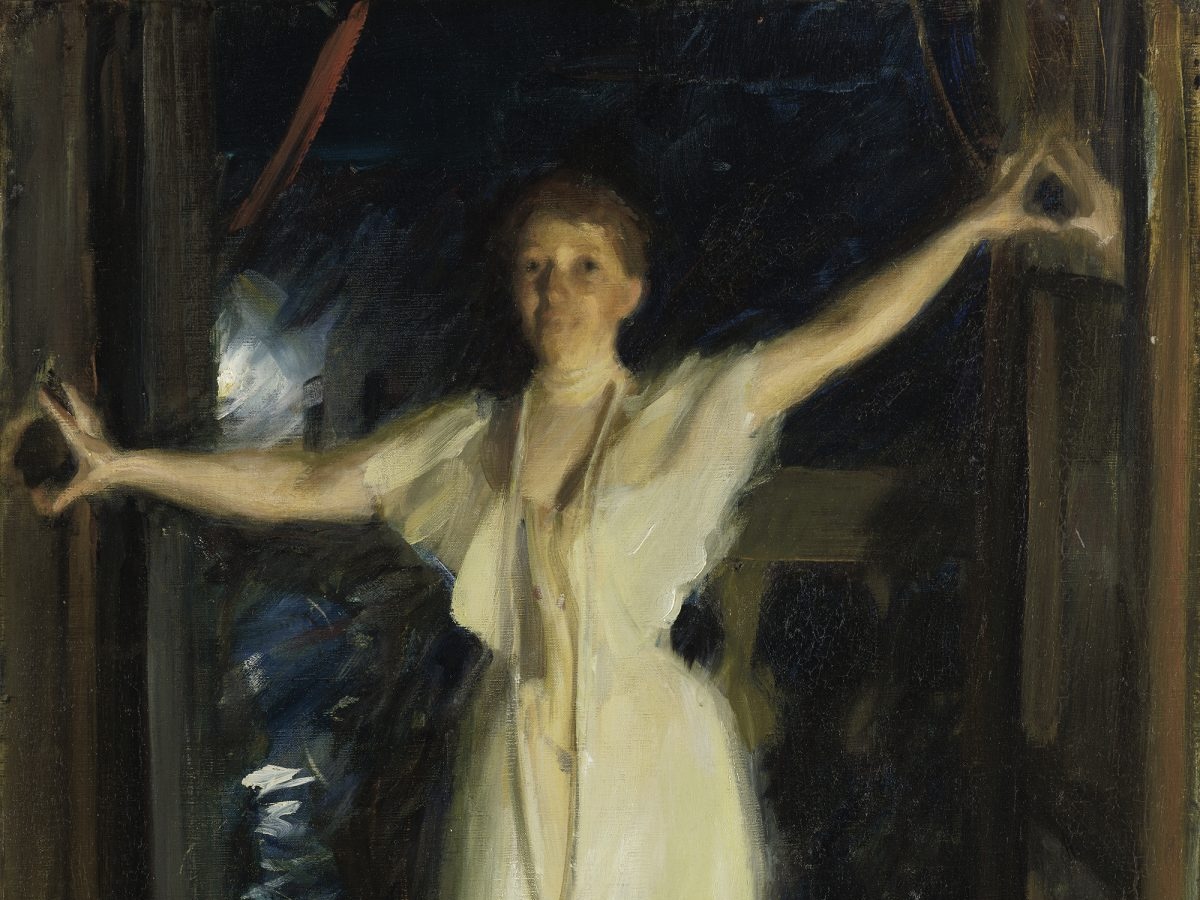

One of the most impressive aspects of the book is its use of primary sources, especially given that Gardner published very little publicly about herself and requested that her private correspondence be destroyed after her death. Still, Dykstra mines a wealth of letters, diaries, and other materials from people in Gardner’s orbit to reconstruct her subject’s multifaceted, larger-than-life persona. As a notable supporter of music and literature in addition to visual art, Gardner was extremely well connected, and communiqués from long-term friends like Henry James and John Singer Sargent offer enticing glimpses into their distinct personalities as they elucidate the intimacy between patron and artist.

Crucially, Gardner’s main art dealer in Europe, Bernhard Berenson, kept his employer’s letters. They reveal her visceral, insatiable hunger for art as she worked to grow her collection. Whether facing import taxes, building delays, or searing criticism of everything from her looks to her ambition, Gardner bristles against and eventually triumphs over anything that stands in her path. What kind of woman was she? Dykstra leaves us room to decide for ourselves.

Regardless, like so many in her time, I finished the book with respect for Gardner’s steadfast vision. In a rare surviving letter that she wrote to a friend near the end of her life, she wrote: “Years ago, I decided that the greatest need in our country was art. We were a very young country and had very few opportunities of seeing beautiful things. So I determined to make it my life’s work if I could.” And Dykstra’s book brings us along on Gardner’s fascinating journey to show us how.

Chasing Beauty: The Life of Isabella Stewart Gardner (2024) by Natalie Dykstra is published by Mariner Books and is available online and through independent booksellers.