The concept of an atmospheric energy imbalance is pretty straightforward: We can measure both the amount of energy the Earth receives from the Sun and how much energy it radiates back into space. Any difference between the two results in a net energy imbalance that’s either absorbed by or extracted from the ocean/atmosphere system. And we’ve been tracking it via satellite for a while now as rising greenhouse gas levels have gradually increased the imbalance.

But greenhouse gases aren’t the only thing having an effect. For example, the imbalance has also increased in the Arctic due to the loss of snow cover and retreat of sea ice. The dark ground and ocean absorb more solar energy compared to the white material that had previously been exposed to the sunlight. Not all of this is felt directly, however, as a lot of the areas where it’s happening are frequently covered by clouds.

Nevertheless, the loss of snow and ice has caused the Earth’s reflectivity, termed its albedo, to decline since the 1970s, enhancing the warming a bit.

Vanishing clouds

The new paper finds that the energy imbalance set a new high in 2023, with a record amount of energy being absorbed by the ocean/atmosphere system. This wasn’t accompanied by a drop in infrared emissions from the Earth, suggesting it wasn’t due to greenhouse gases, which trap heat by absorbing this radiation. Instead, it seems to be due to decreased reflection of incoming sunlight by the Earth.

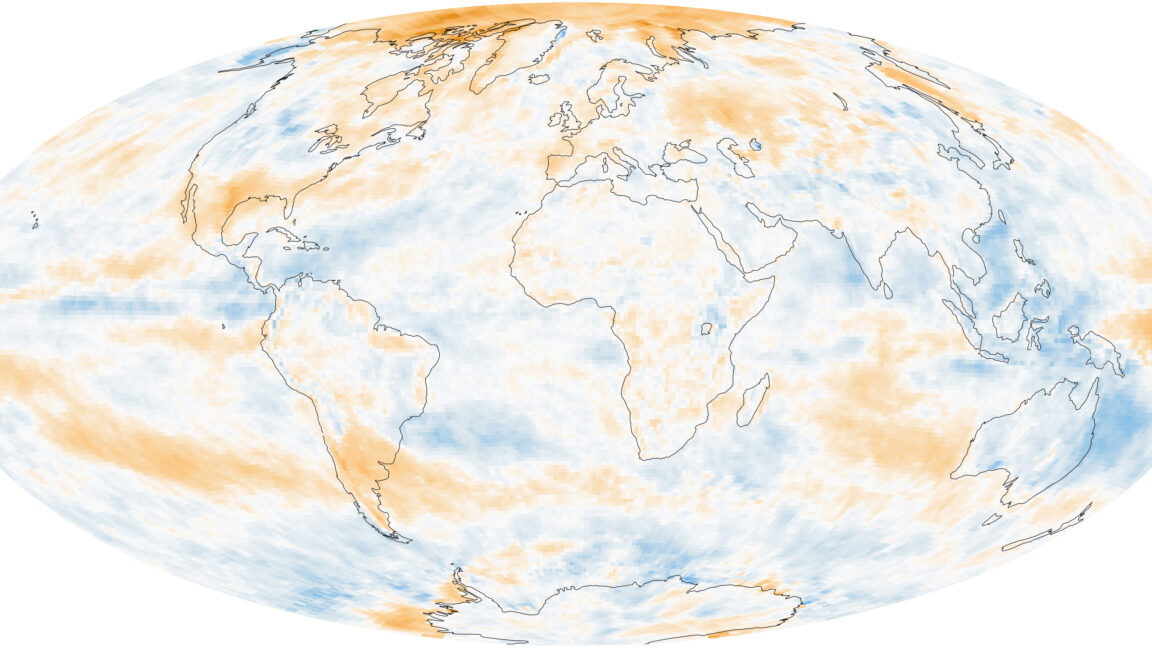

While there was a general trend in that direction, the planet set a new record low for albedo in 2023. Using two different data sets, the teams identify the areas most effected by this, and they’re not at the poles, indicating loss of snow and ice are unlikely to be the cause. Instead, the key contributor appears to be the loss of low-level clouds. “The cloud-related albedo reduction is apparently largely due to a pronounced decline of low-level clouds over the northern mid-latitude and tropical oceans, in particular the Atlantic,” the researchers say.