So steeped are we now in technologically sophisticated persuasion — over one million memes of all sorts shared each day on Instagram alone — that viewing the unpolished and sometimes outlandish propaganda of former times can prompt surprise. Who could have believed that? This is precisely what people 50 years hence are going to say about the digital swill we so readily swallow today. Promise.

For now, we can only prognosticate on this speculative future by looking back. Propagandopolis: A Century of Propaganda from Around the World, a globe-spanning selection of visual persuasions from the early 20th century to now, is a travelogue to disinformation’s past. Culled by Bradley Davies from the online resource and reprint store of the same name, each page of this colorful little handbook of lies fascinates at the same time that it instructs — about historical movements we may have forgotten or never known in the first place, and by extension about our own gullibility to alluring yet biased imagery.

Organized alphabetically by country, starting with Afghanistan and ending with Zimbabwe, the variously beautiful, shocking, dismaying, or quaint images are contextualized with capsule histories of their precipitating circumstances. We learn that one of the most familiar propaganda posters in this collection, the American World War II icon “Loose lips might sink ships,” was designed by Seymour Rinaldo Goff, head of the art department at giant distiller Seagram’s, which was then able to leverage its unique marketing reach to assist with dissemination. In another example, a 1950 Israeli poster shows a faceless Arab soldier from behind a menacing representation of Israel while ships disgorge streams of new immigrants into the state, all beneath the slogan “Growth versus siege!”; the image directly informs current events — it was produced by the Mapai Party, which held power for decades after winning in Israel’s first election the previous year, and its platform was national defense, population growth, and the economy. In the brief text accompanying the image, the general background to the horrific conflict currently raging in the region is succinctly conveyed.

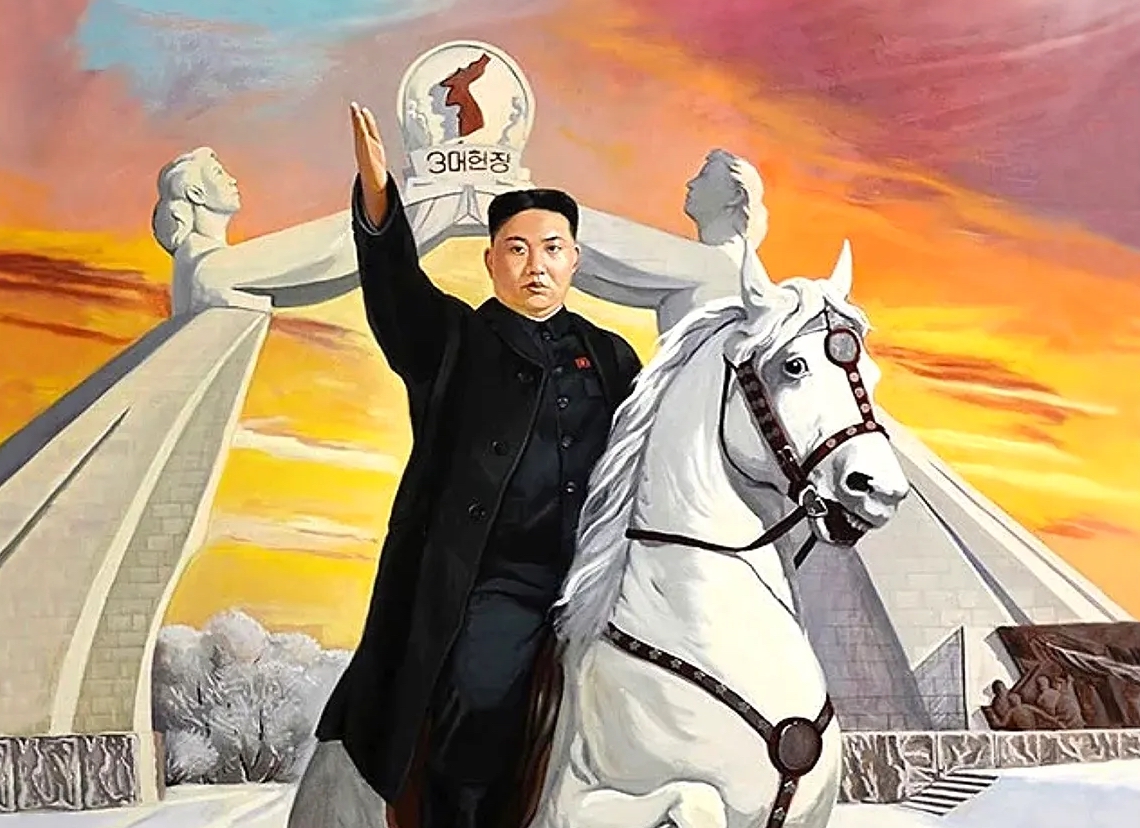

The cruelest and most beneficent regimes are equally responsible for some of the most ravishing images. A 1972 poster from the USSR, its design a nod to Rodchenko and the national aesthetic, shows a worker raising a muscled fist against a Ku Klux Klan member, with the legend “No to racism!” Two depictions from the 1940s glorifying Francisco Franco’s fascist rule are deceitfully luscious — the dictator draped in an absurdly long Spanish flag against a backdrop of roiling storm clouds; a stylized Death on horseback flying over a globe consumed by fiery conflict except for peaceful Spain — while a 1999 painting from Iraq picturing Saddam Hussein in a Mesopotamian chariot wielding a bow and arrow while missiles and warplanes fill the sky is both goofy and gorgeous, as well as a warning about the disastrous fates that so often befall cults of personality. (Turns out a populace will only tolerate absolutism for so long when it ends in savagery to themselves as well as to their enemies; Saddamism was put to death along with its charismatic creator in 2006.)

The welcome inclusion of work from collectives such as San Francisco’s social-justice Fireworks Graphics Collective, the feminist Heresies, and from Emory Douglas’s work on behalf of the Black Panther Party show American design as responsive to a long international history of graphics in service to promoting social issues, which are the basis of many of the book’s other examples of propaganda, no matter the era or location. It’s startling to see how many of the problems addressed during more than a century of murals, political cartoons, leaflets, and posters are still germane to this moment. Just one example is the 1981 Heresies graphic, in a retro 1950s style, in which one woman cautions another about the traditionally handsome man in the foreground: “Careful, honey, he’s anti-choice.”

Robert Peckham, historian and author of Fear: An Alternative History of the World, provides the informative introduction to the subject of visual propaganda, “Fear, Truth, and the Spectacular History of Propaganda.” It traces the genre’s beginning to the development of movable type and Martin Luther’s use of it to produce his Flugschriften (“flying writings”) pamphlets. Later, during the French Revolution, a variety of visual signals such as wearing tricolor cockades and the cotton pantaloons of the working class were deployed to indicate and enforce group affiliation. The First World War added fuel to the engine of propaganda as a consolidated and official means of achieving state goals: “In 1917, President Wilson had set up a Committee on Public Information (CPI) with a remit to influence public opinion in support of the war through the distribution of pamphlets, posters, radio broadcasts, films, and public talks.” Propaganda was off to the races.

As Peckham reminds us, art is also ultimately a tool to influence opinion and foment action; it “exists in an ambiguous space between propaganda and commerce.” There will never be an end to manipulation by image. All we can do is understand its past in the hope of being able to read its future when it comes.

Propagandopolis: A Century of Propaganda from Around the World by Bradley Davies (2024) is published by Fuel and is available online and in bookstores.