There are “self-made men,” and then there are self-made legends: artists who mythologize themselves so thoroughly that they seem to escape the confines of normal personhood. Weegee was one such artist. “My real name is Arthur Fellig. But I don’t even recognize it when I see it,” he asserted in a 1965 interview. Famous for his early career as a nighttime news photographer — shooting grisly images of fires, murders, and other tragedies in high contrast — Weegee allegedly earned his name for his uncanny ability to show up at scenes of disaster even before the police, prompting some to liken him to an Ouija board.

For most of his early career, the photographer lived on the precarious margins of society, always on the go and often in a state of near homelessness. (He also worked odd jobs, including as a movie theater fiddler for silent films.) Weegee’s first photographic employer, Acme Newspictures, wouldn’t send him out during the day unless he wore a white shirt and tie, so he began taking to the streets at night, flying from disaster to disaster in a rented ambulance that he turned into a darkroom: A three-alarm fire brought him a three-dollar bonus, while a five-alarm fire got him five. Weegee worked hard to cultivate his identity as an eccentric. Though he was neither able nor willing to become an integrated member of New York City’s art world society, the photographer branded himself “Weegee the Famous” and readily took up the role of an object of curiosity among the elite. Eventually, he moved to Hollywood, where he even had a brief stint as a character actor.

Weegee: Society of the Spectacle, a career-spanning exhibition of the photographer’s work now on view at the International Center of Photography, aims to bridge the gap between this early Weegee and the one who went on to photograph Hollywood stars and politicians. Critics have tended to dismiss late-career Weegee, as if his tawdry gaze became intolerable once it left the streets and entered the studio. Perhaps this is because his career spans an art historical divide of its own: Early Weegee can be justified in the context of 1930s documentary photography, specifically the genre as it was reimagined and embraced by the European avant-garde. In this reading, Weegee is the American counterpart to Brassaï, whose nighttime images of the Parisian underworld were embraced by the Surrealists. (Weegee’s own portraits of Salvador Dalí, on view in a Scoop! magazine photo feature, underscore this parallel.) There is cultural cachet to this connection, and Modernism’s anti-establishment street cred indeed gets lost in Hollywood.

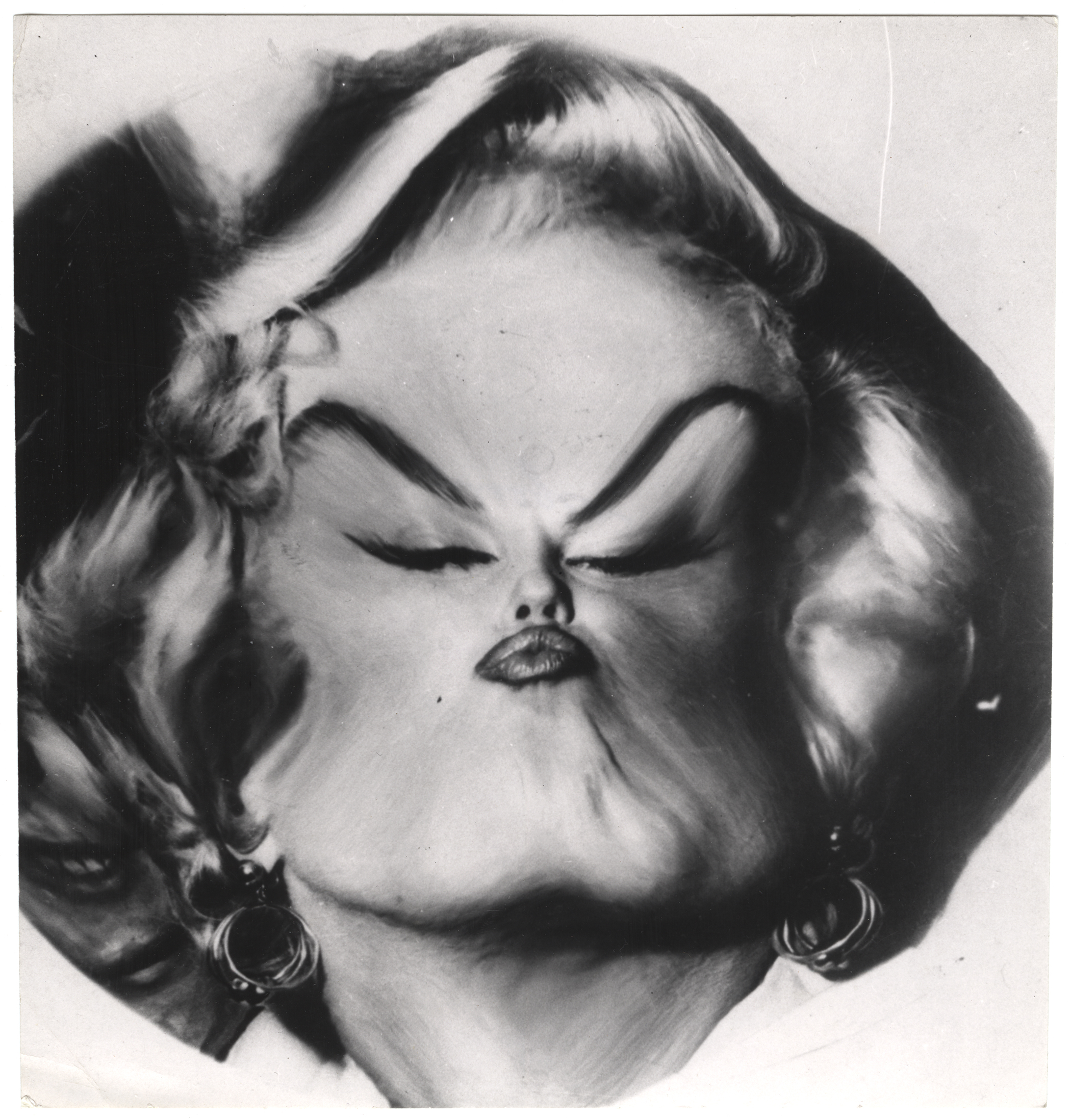

But if we look at what comes later, as this exhibition encourages us to, something curious emerges: a sense of Weegee as a proto-Pop Artist. Facing a wall of his distorted portraits, we come face to face with images of pop culture (and Pop Art) icons like Marilyn Monroe and Jackie Kennedy. Suddenly, we recover something curiously Warholian in Weegee’s early photos of criminals and murderers: Are these not the gleeful precursors to the Pop Art paragon’s 13 Most Wanted Men (1964) and Death and Disasters (1962–67)? By embracing the spectacle of horror through the hyperbolic, larger-than-life persona that Weegee constructed for himself, does the photographer not occupy an odd middle ground between the news media and its parody? Was Weegee a Pop artist? That question would have seemed strange to me six months ago — but after seeing his 1965 portrait “For Senator Andy Warhol,” I’m left wondering.

Weegee: Society of the Spectacle continues at the International Center of Photography (84 Ludlow Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan) through May 5. The exhibition was curated by Clément Chéroux.